Lecture: Hand Hygiene Practices

Learning Objectives

- Master proper hand washing.

- Evaluate sanitizer efficacy factors.

- Analyze compliance monitoring strategies.

- Implement hygiene best practices.

Prerequisite Knowledge

- Basic microbiology principles.

- Understanding of pathogen transmission.

- Familiarity with hospital environments.

Section 1: The Foundation of Safety - Hand Washing

The Cornerstone of Infection Prevention: The Science and Practice of Hand Washing

Hand washing is not merely a ritualistic cleansing; it is the single most effective, evidence-based intervention to prevent the spread of healthcare-associated infections (HAIs). Its simplicity belies a sophisticated interplay of chemical and mechanical forces that physically remove and inactivate pathogens. Understanding this process is fundamental to its correct application and to appreciating its non-negotiable role in patient safety. While modern medicine boasts incredible technological advancements, the deliberate act of washing hands with soap and water remains a primary defense against microbial threats.

The Science of Soap and Water: A Microscopic Battle

To truly grasp the power of hand washing, we must move beyond the macroscopic view of 'clean' and understand the microscopic battle being waged. Water alone is a poor cleaning agent for hands in a clinical setting because many germs and organic materials are not water-soluble. This is where soap becomes the critical component.

- Surfactant Chemistry: Soap molecules are amphiphilic, meaning they have a "water-loving" (hydrophilic) head and a "water-hating" or "oil-loving" (lipophilic) tail. This dual nature is the key to their effectiveness. The lipophilic tails are drawn to the oils and fats on our skin, as well as the lipid membranes that envelop many viruses (including coronaviruses and influenza) and bacteria.

- Micelle Formation: When you lather soap with water, these molecules form tiny spheres called micelles. The lipophilic tails point inward, trapping oils, dirt, and microorganisms. The hydrophilic heads point outward, allowing the entire micelle—with its trapped payload of pathogens—to be easily washed away by the rinsing water. This process is known as emulsification. It doesn't just kill germs; it physically removes them from the skin's surface.

- The Role of Mechanical Friction: The act of rubbing your hands together is not passive. This mechanical friction is crucial for dislodging microorganisms and debris from the skin's crevices and under the fingernails. It ensures the soap and water mixture reaches all surfaces and helps lift the transient microbes into the micelles for removal. The World Health Organization's (WHO) prescribed steps are specifically designed to maximize this mechanical action across every part of the hands.

Transient vs. Resident Flora: Knowing Your Enemy

The microbial population on our hands is not uniform. It's crucial to distinguish between two categories:

- Transient Flora: These are microorganisms acquired from the environment—by touching a contaminated surface, a patient's skin, or medical equipment. They colonize the superficial layers of the skin and are the organisms most frequently associated with HAIs. Transient flora are the primary target of routine hand hygiene, as they are easily picked up, readily transmitted, and can be effectively removed with proper hand washing (Boyce & Pittet, 2002).

- Resident Flora: These are part of our normal skin microbiome, residing in deeper layers of the epidermis and hair follicles. They are not typically associated with HAIs in immunocompetent hosts and are more difficult to remove. While routine hand washing reduces their numbers, their complete elimination is neither possible nor desirable. Surgical hand antisepsis, a more rigorous procedure, is required to significantly reduce the resident flora before invasive procedures.

The WHO "5 Moments for Hand Hygiene": A Framework for Action

Knowing *how* to wash hands is useless without knowing *when*. The WHO's "5 Moments for Hand Hygiene" provide a clear, evidence-based, and globally recognized framework to apply hand hygiene precisely at the points of care where it is most needed to interrupt pathogen transmission (Pittet et al., 2009).

- Before Touching a Patient: Why? To protect the patient against harmful germs carried on your hands. This is done before any direct contact, such as shaking hands, taking vital signs, or performing a physical examination.

- Before a Clean/Aseptic Procedure: Why? To protect the patient against harmful germs, including their own, from entering their body during a procedure. This is critical before actions like inserting a catheter, administering an injection, or dressing a wound.

- After Body Fluid Exposure Risk: Why? To protect yourself and the healthcare environment from harmful patient germs. This is performed immediately after any potential contact with blood, urine, wound drainage, or other bodily fluids, even if gloves were worn.

- After Touching a Patient: Why? To protect yourself and the healthcare environment from harmful patient germs. This is done after any direct contact with the patient has concluded.

- After Touching Patient Surroundings: Why? To protect yourself and the healthcare environment. Pathogens can survive on inanimate objects like bed rails, overbed tables, and IV pumps. This moment acknowledges that the patient's immediate environment is an extension of the patient themselves and is a frequent source of contamination.

The Technique: A Step-by-Step Masterclass

Effective hand washing is a skill that requires precision and attention to detail. The entire process should take 40-60 seconds—the time it takes to sing "Happy Birthday" twice. Each step is designed to decontaminate a specific area of the hands.

- Wet hands with clean, running water.

- Apply enough soap to cover all hand surfaces.

- Rub hands palm to palm. (Creates initial lather)

- Right palm over left dorsum with interlaced fingers and vice versa. (Cleans the back of hands and between fingers)

- Palm to palm with fingers interlaced. (Cleans between fingers from the front)

- Backs of fingers to opposing palms with fingers interlocked. (Crucial for cleaning fingertips and knuckles)

- Rotational rubbing of left thumb clasped in right palm and vice versa. (Decontaminates the thumbs, an often-missed area)

- Rotational rubbing, backwards and forwards with clasped fingers of right hand in left palm and vice versa. (Cleans under the fingernails)

- Rinse hands thoroughly with water, keeping hands pointed downwards to prevent recontamination of arms.

- Dry thoroughly with a single-use towel. This is a critical step; damp hands can transfer microbes more easily.

- Use the towel to turn off the faucet. This prevents re-contaminating your clean hands from the faucet handle.

Clinical Examples

Scenario 1: Entering a Patient Room. A nurse enters a patient's room to check their IV pump. The patient is asleep. The nurse adjusts the pump settings without touching the patient. According to the "5 Moments," hand hygiene is required upon entry (Moment 1: Before touching a patient, even if contact is anticipated but doesn't occur) and upon leaving (Moment 5: After touching patient surroundings).

Scenario 2: Wound Care. A healthcare assistant is tasked with changing a patient's wound dressing. They must perform hand hygiene before gathering supplies (to prevent contaminating clean supplies), again immediately before starting the procedure (Moment 2), and finally after removing their gloves and completing the task (Moment 3).

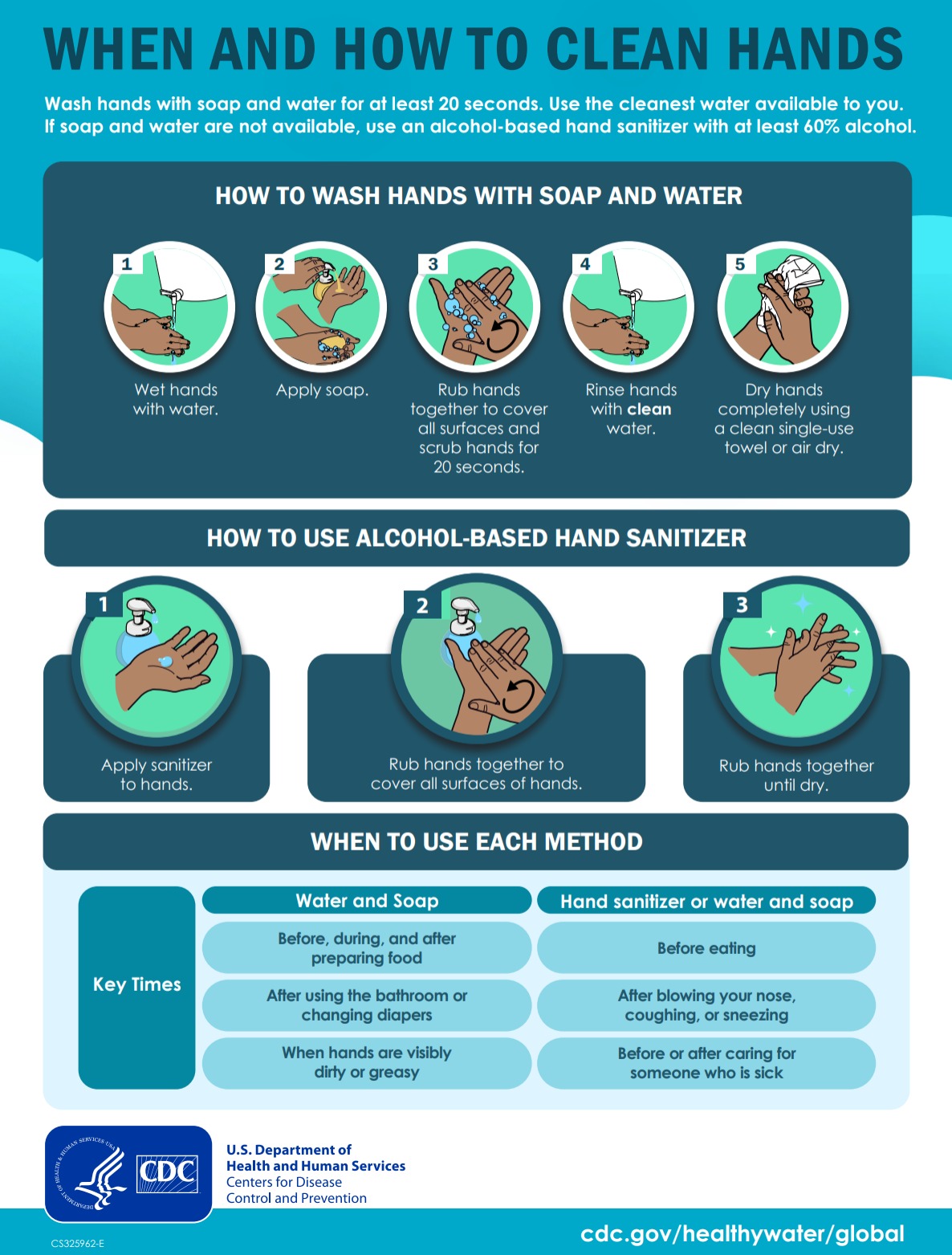

Hand Hygiene Poster

Did You Know?

The father of hand hygiene, Dr. Ignaz Semmelweis, discovered its life-saving potential in 1847. He observed that maternal mortality from puerperal fever was three times higher in a Vienna hospital ward attended by doctors and medical students coming directly from autopsies compared to a ward attended by midwives. He hypothesized that "cadaverous particles" were being transmitted. By mandating hand washing with a chlorinated lime solution, he reduced the mortality rate from 18% to nearly 1%. Tragically, his groundbreaking work was rejected by the established medical community, and he died in an asylum, vindicated only decades later by the work of Lister and Pasteur (Semmelweis, 1861).

Section 1 Summary

- Hand washing physically removes transient pathogens through the chemical action of soap (emulsification) and mechanical friction.

- The primary goal is to remove transient flora, which are acquired from the environment and cause most HAIs.

- The WHO's "5 Moments for Hand Hygiene" provide a clear, action-oriented framework for when to perform hand hygiene.

- Proper technique, covering all surfaces of the hands for a duration of 40-60 seconds, is essential for effectiveness.

- Drying hands with a single-use paper towel and using it to turn off the faucet are critical final steps to prevent recontamination.

Reflective Questions

- Think about your last clinical shift or work day. Can you identify missed opportunities for hand hygiene based on the "5 Moments"? What was the primary barrier in those instances?

- How can the specific, step-by-step hand washing technique be turned into an automatic, ingrained habit rather than a checklist to be remembered? What memory aids or practice techniques could you use?

Section 2: Sanitizer Efficacy and Application

Alcohol-Based Hand Rubs (ABHRs): Efficacy, Limitations, and Proper Use

While soap and water are fundamental, the advent and widespread adoption of Alcohol-Based Hand Rubs (ABHRs) have revolutionized hand hygiene practices. In most clinical situations where hands are not visibly soiled, ABHRs are the preferred method due to their broad-spectrum efficacy, speed of use, and increased accessibility at the point of care. However, their effectiveness is highly dependent on their formulation, the pathogens present, and, most importantly, the technique of application.

Mechanism of Action: Denaturation and Disruption

The primary active ingredients in ABHRs are alcohols, typically ethanol, isopropanol, or a combination. Unlike soap, which primarily removes germs, alcohol acts as a potent biocide, killing them directly.

- Protein Denaturation: The core mechanism is the denaturation of microbial proteins and enzymes. Alcohol molecules disrupt the intramolecular hydrogen bonds that maintain a protein's three-dimensional structure. This causes the proteins to unfold and coagulate, rendering them non-functional. Essential cellular processes halt, leading to rapid cell death.

- Membrane Disruption: Alcohol also disrupts the lipid membranes of bacteria and the lipid envelopes of certain viruses (e.g., influenza, herpes, HIV, and coronaviruses). By dissolving these fatty outer layers, the pathogen's integrity is compromised, leading to its inactivation. This is a key reason why ABHRs are so effective against many common respiratory viruses.

The Crucial Importance of Alcohol Concentration

Not all alcohol concentrations are equally effective. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and WHO recommend products containing 60% to 95% alcohol for use in healthcare settings (Boyce & Pittet, 2002). The science behind this specific range is critical:

- Below 60%: The concentration is too low to be reliably effective. The germicidal activity drops significantly, making the product inadequate for clinical use.

- Within 60-95%: This is the optimal range for antimicrobial efficacy.

- The Water "Paradox": Pure 100% alcohol is surprisingly *less* effective as a disinfectant than a solution of ~70% alcohol and 30% water. This is because water acts as a catalyst for protein denaturation and is necessary to help the alcohol penetrate the microbial cell wall. In the absence of water, pure alcohol causes rapid surface protein coagulation, which can actually form a protective layer that prevents the alcohol from reaching the cell's interior.

Spectrum of Activity: What ABHRs Can and Cannot Do

An understanding of an ABHR's spectrum of activity is vital for making correct clinical decisions. While effective against a wide range of pathogens, they have significant limitations.

- Effective Against: Most gram-positive and gram-negative bacteria (including multi-drug resistant strains like MRSA and VRE), enveloped viruses (Influenza, Coronaviruses, RSV, HIV), and most fungi.

- Poorly Effective or Ineffective Against:

- Bacterial Spores: Organisms like Clostridioides difficile (C. diff) form highly resistant spores that are impervious to alcohol. The spore's tough outer coat protects it from denaturation. In cases of known or suspected C. diff, vigorous hand washing with soap and water is mandatory to physically remove the spores.

- Protozoan Oocysts: Pathogens like Cryptosporidium are also resistant to alcohol.

- Some Non-enveloped Viruses: Viruses that lack a lipid envelope, such as Norovirus and Poliovirus, are much less susceptible to alcohol's effects. While some high-concentration ABHRs show partial activity, soap and water remain the superior method for removing these viruses (Sickbert-Bennett et al., 2005).

The Cardinal Rule: No Visible Soiling

The single most important rule governing the use of ABHRs is that they are only appropriate when hands are not visibly soiled. Organic matter, such as blood, dirt, or other bodily fluids, can inactivate the alcohol and physically shield microorganisms from contact with the sanitizer. The proteins in organic matter can react with the alcohol, reducing its effective concentration. Therefore, if there is any visible contamination, hands *must* be washed with soap and water.

Proper Application Technique: It's All About Coverage and Contact Time

Simply squirting a small amount of sanitizer on the palms is insufficient. The application technique is just as rigorous as that for hand washing and relies on two principles: complete coverage and adequate contact time.

- Apply a sufficient volume of product (typically a palmful, or 3-5 mL) to one palm.

- Dip fingertips of the opposite hand in the sanitizer to decontaminate under the nails.

- Rub hands palm to palm.

- Rub over the back of each hand with the opposite palm, fingers interlaced.

- Rub palm to palm with fingers interlaced.

- Rub the backs of fingers on the opposing palms.

- Rub each thumb rotationally.

- Continue rubbing all surfaces until the product is completely dry. This step is non-negotiable and should take 20-30 seconds. Do not wave hands in the air or wipe them on your uniform to speed up drying. The "wet time" is the contact time required for the alcohol to kill the pathogens. Wiping it off prematurely negates the entire process.

Clinical Examples

Case Study: A Norovirus Outbreak. A hospital ward is experiencing an outbreak of norovirus gastroenteritis. Staff diligently increase their use of the ABHR dispensers located in every room. However, transmission continues. The Infection Prevention team intervenes and mandates a "soap and water only" policy for hand hygiene for all staff on that ward. The outbreak subsides within a week. This illustrates the critical importance of selecting the correct hand hygiene method based on the specific pathogen of concern.

Practical Application: Inadequate Volume. A clinician dispenses a dime-sized amount of ABHR and rubs it for 5 seconds. Their hands feel dry almost immediately. While they may feel they have performed hand hygiene, the volume was too small to cover all surfaces, and the contact time was far too short to achieve a significant microbial kill. This is a common error that leads to a false sense of security.

Did You Know?

The gel formulation of many common hand sanitizers was a significant innovation. The gelling agent, typically a polymer like carbomer, allows for a higher concentration of alcohol to be used without it immediately evaporating or running off the hands. This ensures a longer contact time. It also allows for the inclusion of emollients like glycerin and aloe vera, which help to counteract the drying effect of alcohol and improve skin tolerability, a key factor in promoting compliance.

Section 2 Summary

- ABHRs are the preferred method of hand hygiene when hands are not visibly soiled, working by denaturing microbial proteins.

- The effective alcohol concentration is between 60% and 95%; water is a necessary component for optimal efficacy.

- ABHRs are ineffective against spore-forming bacteria like C. difficile and certain non-enveloped viruses like Norovirus, necessitating hand washing in these situations.

- Proper technique requires sufficient product volume to cover all hand surfaces and rubbing until the hands are completely dry (20-30 seconds) to ensure adequate contact time.

- If hands are visibly soiled with dirt or organic matter, they must be washed with soap and water.

Reflective Questions

- Considering the limitations of ABHRs, what communication strategies could be used on a hospital-wide level to ensure staff can quickly identify situations (e.g., a patient with diarrhea) where they must switch from ABHR to soap and water?

- How do factors like skin condition (dryness, cracking) influence a healthcare worker's willingness to use ABHRs frequently? What role does product selection and availability of moisturizers play in an effective hand hygiene program?

Section 3: The Human Factor - Compliance Practices and Monitoring

Bridging the "Knowing-Doing Gap": Strategies for Improving and Sustaining Hand Hygiene Compliance

We have established the "why" and "how" of hand hygiene. The most complex challenge, however, is ensuring it is performed consistently and correctly by every healthcare worker, for every patient, every single time. Decades of research have shown that despite near-universal knowledge of its importance, hand hygiene compliance in healthcare settings often remains below 50% in the absence of a dedicated improvement program (Pittet et al., 2009). This section delves into the barriers to compliance and the multimodal strategies required to foster a true culture of safety where hand hygiene is an ingrained, non-negotiable practice.

Understanding the Barriers to Compliance

To fix the problem, we must first understand its roots. Non-compliance is rarely a result of willful negligence; it is most often a complex interplay of individual and systemic factors.

- Individual Factors:

- High Workload: Being "too busy" is the most commonly cited reason for non-compliance. In a high-pressure environment, hand hygiene can be overlooked in favor of more immediate patient care tasks.

- Skin Irritation: Frequent washing or sanitizer use can lead to dermatitis, making the process painful and creating a disincentive.

- Forgetfulness: In a fast-paced workflow with many competing priorities, hand hygiene can simply be forgotten.

- Misinformation: A common misconception is that wearing gloves obviates the need for hand hygiene. In reality, gloves are not foolproof, can have micro-perforations, and hands can be contaminated during glove removal.

- Lack of Role Models: If senior physicians or nurses are seen skipping hand hygiene, it sends a powerful message that the rules are not absolute.

- Systemic/Institutional Factors:

- Inaccessible Supplies: Sinks that are poorly located, ABHR dispensers that are empty, or a lack of paper towels create significant barriers. Hand hygiene must be convenient and integrated into the workflow. The single most important system change is making ABHR available at the point of care.

- Lack of Institutional Priority: If hospital leadership does not actively champion, fund, and prioritize hand hygiene, staff will perceive it as a low-priority task.

- No Accountability: If compliance is not measured and no feedback is given, there is no impetus for change.

The Multimodal Strategy: A Bundled Approach to Change

There is no single "magic bullet" to improve compliance. The WHO and other leading bodies advocate for a multimodal strategy that addresses the complex barriers simultaneously. The key components include:

- System Change: This is the foundation. It involves ensuring the right infrastructure is in place. This means installing ABHR dispensers at every patient bedside and point of care, keeping them consistently filled, and ensuring sinks are well-stocked and functional. The goal is to make the right choice the easy choice.

- Training and Education: This goes beyond an annual PowerPoint presentation. Effective education should be ongoing, interactive, and focus not just on the "how" but the "why." It should include updates on hospital HAI rates, case studies demonstrating the impact of hand hygiene, and hands-on practice sessions.

- Monitoring and Performance Feedback: "What gets measured gets improved." This is a critical component for driving change. The data collected must be fed back to frontline staff in a timely, consistent, and non-punitive manner.

- Direct Observation: This is considered the "gold standard." Trained, validated observers (often "secret shoppers") covertly watch staff during routine care and record compliance with the 5 Moments. Pros: It provides rich, contextual data and can assess technique quality. Cons: It is resource-intensive and highly susceptible to the Hawthorne effect—the tendency for people to behave differently when they know they are being watched, which can artificially inflate compliance rates.

- Automated Monitoring Systems: Technology is providing new solutions. These can include electronic systems that count dispenser activations, systems that track room entry/exit and dispenser use via badges, or even video-based AI monitoring. Pros: They can collect vast amounts of objective data without direct human bias. Cons: They can be expensive, raise privacy concerns, and typically cannot measure the quality of the hand hygiene event or confirm if it occurred at the correct "moment."

- Product Volume Measurement: This is an indirect method that involves tracking the amount of soap and ABHR consumed per patient-day. Pros: It is simple and inexpensive. Cons: It provides no information on who is using the product or if it is being used correctly.

- Reminders and Communications: Placing visual cues, posters, and reminders in the workplace helps keep hand hygiene top-of-mind. These should be refreshed periodically to avoid "alert fatigue."

- Institutional Safety Climate: This is the overarching cultural component. Leadership at all levels must visibly champion hand hygiene. It must become a shared value, where staff feel empowered to remind each other (peer-to-peer accountability) and even remind their superiors without fear of reprisal. A "Just Culture" approach is essential, focusing on identifying and fixing system failures rather than blaming individuals for lapses.

Patient Empowerment: A Key Ally

Patients and their families can be powerful partners in infection prevention. Programs that encourage patients to ask their healthcare providers, "Did you wash your hands?" can be effective. However, this must be implemented carefully within a supportive institutional culture. Staff must be trained to receive this question as a welcome safety check, not as an accusation, and patients must be made to feel genuinely safe and empowered to ask.

Clinical Examples

System Change in Action: An ICU has a hand hygiene compliance rate of 45%. The unit manager observes that nurses frequently have their hands full when entering and exiting rooms, making it difficult to use the wall-mounted dispensers. The hospital invests in installing ABHR dispensers on IV poles and mobile computer workstations. Within three months, compliance measured by direct observation increases to 75%, demonstrating the power of integrating hygiene into the existing workflow.

Effective Feedback Loop: Instead of individual report cards, a hospital posts anonymized, unit-level compliance data publicly each month. The data is color-coded (green for meeting goal, yellow for approaching, red for needing improvement) and shows the unit's trend over time. This fosters a sense of collective ownership and friendly competition between units, leading to a hospital-wide improvement in compliance rates.

Did You Know?

The "Hawthorne effect" was first described during experiments at the Hawthorne Works, a factory near Chicago, in the 1920s and 30s. Researchers found that workers' productivity improved whenever changes were made to their environment, not because of the changes themselves, but because they were being observed. In hand hygiene monitoring, this effect can be so profound that some studies show observed compliance rates are double or even triple the rates when staff are unobserved, making it a major challenge for accurate measurement and a strong argument for supplementing direct observation with other monitoring methods.

Section 3 Summary

- Hand hygiene compliance is a complex problem with both individual (e.g., workload, forgetfulness) and systemic (e.g., access to supplies) barriers.

- A multimodal strategy that combines system change, training, monitoring with feedback, reminders, and a positive safety climate is the most effective approach to improvement.

- Monitoring methods like direct observation, automated systems, and product measurement each have distinct advantages and disadvantages.

- Performance feedback to frontline staff should be regular, transparent, and non-punitive to be effective.

- Strong leadership and a "Just Culture" that focuses on systems instead of blame are critical for creating sustainable change and a true culture of patient safety.

Reflective Questions

- If you were tasked with designing a new hand hygiene campaign for your hospital, which component of the multimodal strategy would you prioritize first and why?

- How can you personally contribute to a positive safety climate regarding hand hygiene? What would it take for you to feel comfortable reminding a senior colleague to perform hand hygiene if you observed a lapse?

Glossary of Key Terms

- Alcohol-Based Hand Rub (ABHR)

- An alcohol-containing preparation designed for application to the hands to inactivate microorganisms and/or temporarily suppress their growth.

- Transient Flora

- Microorganisms that colonize the superficial layers of the skin, are acquired through direct contact with the environment, and are responsible for most healthcare-associated infections.

- Resident Flora

- Microorganisms that are permanent residents of the skin, living in deeper layers. They are not easily removed and are less likely to cause infection.

- Healthcare-Associated Infection (HAI)

- An infection that a patient acquires during the course of receiving treatment for other conditions within a healthcare setting. Also known as a nosocomial infection.

- 5 Moments for Hand Hygiene

- A framework developed by the World Health Organization that defines the key moments when healthcare workers should perform hand hygiene to prevent pathogen transmission.

- Hawthorne Effect

- The alteration of behavior by the subjects of a study due to their awareness of being observed.

References

- Boyce, J. M., & Pittet, D. (2002). Guideline for Hand Hygiene in Health-Care Settings: Recommendations of the Healthcare Infection Control Practices Advisory Committee and the HICPAC/SHEA/APIC/IDSA Hand Hygiene Task Force. MMWR. Recommendations and Reports, 51(RR-16), 1–45.

- Pittet, D., Allegranzi, B., Boyce, J., & World Health Organization World Alliance for Patient Safety First Global Patient Safety Challenge Core Group of Experts. (2009). The World Health Organization guidelines on hand hygiene in health care and their consensus recommendations. Infection Control and Hospital Epidemiology, 30(7), 611–622.

- Semmelweis, I. (1861). Die Aetiologie, der Begriff und die Prophylaxis des Kindbettfiebers [The Etiology, Concept, and Prophylaxis of Childbed Fever]. C.A. Hartleben.

- Sickbert-Bennett, E. E., Weber, D. J., Gergen-Teague, M. F., Sobsey, M. D., Samsa, G. P., & Rutala, W. A. (2005). Comparative efficacy of hand hygiene agents in the reduction of bacteria and viruses. American Journal of Infection Control, 33(2), 67–77.

- World Health Organization. (2009). WHO Guidelines on Hand Hygiene in Health Care: First Global Patient Safety Challenge, Clean Care is Safer Care. World Health Organization.